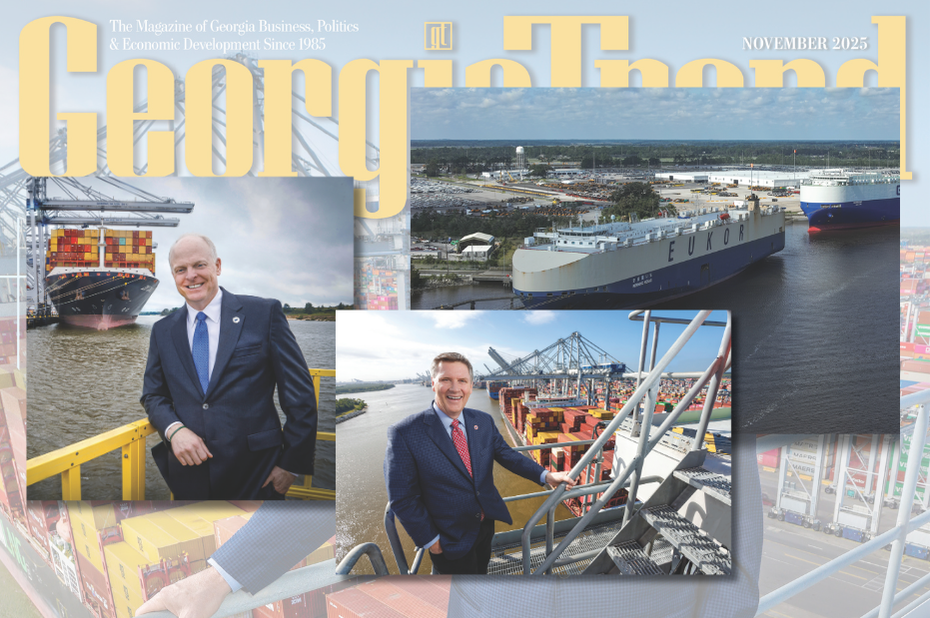

Navigating the Future

Georgia’s ports are full steam ahead for growth, despite the uncertainty of tariffs and other global events.

Imagine being tasked with seeing a decade into the future of global shipping, with billions of dollars in infrastructure construction riding on the accuracy of your prediction. Not easy, but if you get it right, you end up with things like the fastest-growing container port in the nation (the Port of Savannah) and the country’s largest automotive and heavy equipment specialty port (the Port of Brunswick). And those two ports, in turn, become a massive engine driving Georgia’s economy.

Imagine being tasked with seeing a decade into the future of global shipping, with billions of dollars in infrastructure construction riding on the accuracy of your prediction. Not easy, but if you get it right, you end up with things like the fastest-growing container port in the nation (the Port of Savannah) and the country’s largest automotive and heavy equipment specialty port (the Port of Brunswick). And those two ports, in turn, become a massive engine driving Georgia’s economy.

“We’re not just looking to satisfy capacity for tomorrow; we need to be 10 years ahead,” says Griffith Lynch, president and CEO of the Georgia Ports Authority, which operates the state’s two deepwater ports and a growing portfolio in inland assets.

As an example, he points to the future Savannah Container Terminal, an entirely new three-berth container facility the GPA plans to build on its land on Hutchinson Island, a mid-river island between Georgia and South Carolina. “From permitting to delivery can be seven to eight years. That’s why we’re permitting that land now and we hope to be building a terminal out there sometime in the 2030s,” he says.

“It’s so rare in today’s environment,” he says of the project. “There’s nowhere else you could build on a greenfield site that is adjacent to a highway. Truck drivers will leave the facility and won’t have to stop until they get to Atlanta.”

New Heights

Another example of planning ahead of need is the upcoming project to raise of the Eugene Talmadge Memorial Bridge that spans the Savannah River. This is a $189 million project that Lynch says the Georgia Department of Transportation expects to begin early in 2026 and to complete by late 2028 or early 2029.

All ships that currently want to call on the Port of Savannah are able to make it under the existing bridge, but shipping lines already have vessels afloat that wouldn’t make it under the span, and the port wants to be ready for them, he notes. The project – which he acknowledges is a temporary fix, but a “long temporary” – will jack the existing bridge up by tightening cables to gain an estimated 20 feet in height. A more permanent solution, possibly involving a tunnel, is years down the road.

Inland Terminals: Cargo at the Appalachian Regional Port in North Georgia. Photo credit: Georgia Ports Authority

“The planning process is a 10-year horizon, and every two years, as a team, we get with our consultants and internally with our engineering team and do our plan, so this year will be focused on 2036,” says Edward McCarthy, chief operating officer for GPA. “We look at [what] the economists and our outside consultants are projecting is going to happen in the Southeast region and then we go back and match that with our projects, saying ‘OK, what is the capacity and the volume that’s going to come into the terminal, and do we have enough capacity in five different areas: berths, gates, yard, rail and warehousing?’”

Current plans already in various stages from planning to construction will take the number of container berths in Savannah from the current seven to 12, McCarthy points out, and those numbers will eventually drive Savannah’s throughput capacity ahead of the New York/New Jersey ports complex. The Northeastern complex cannot feasibly expand its real estate holdings and can only add capacity by what McCarthy calls “densifying.”

Rich in Assets

Not all port assets are on the ocean. GPA operates two inland terminals – essentially a rail hub with a truck gate – in North Georgia and plans to add a third near West Point, about 11 miles from that Georgia city’s Kia assembly plant, McCarthy says. He adds that Georgia, South Carolina and Virginia are the only states he’s aware of with port-owned inland terminals. Other states use private terminals.

A 10-Year Horizon: Edward McCarthy, chief operating officer for the Georgia Ports Authority. Photo credit: Frank Fortune

So, who’s on the hook for the $4.5 billion capital improvement plan underway at the port? Essentially, the port itself, through the funds it generates, often aided by its access to the bond market. That’s where an excellent credit rating helps, and GPA announced in August that S&P Global had assigned its revenue bonds a rating of AA/Stable. Last fall, Moody’s issued an equivalent rating. The massive expense of maintaining the federal waterways themselves, such as channel dredging, is funded with federal tax revenue, and the Georgia DOT picks up much of the tab for port-specific roadway improvements, such as the upcoming raising of the Talmadge Bridge.

To meet warehousing demands, the ports depend largely on private investment. A plea for developers to produce additional warehouse space went out three days after McCarthy took up his duties in 2016, and it’s been answered – loudly. In the past nine years, the area within a 20-mile radius of the port has added just over 100 million square feet of warehouse space, he says, bringing the total to 145 million square feet.

Facing Turbulent Waters

When it comes to planning ahead, what do the ports do about unforeseen national and global events? After all, the current trade war, with its whiplash of on-again, off-again tariffs, wasn’t anticipated 10 years ago.

But advance planning plays its role there, too.

In 2019, the GPA purchased additional land that expanded its flagship Garden City terminal to the west. The increased storage capacity at the terminal was intended to help customers avoid bottlenecks in their own warehousing when seasonal orders came in before it was time to place them on shelves. That capacity proved especially helpful when customers placed massive pre-orders to get ahead of the implementation of tariffs this spring. A U.S. Supreme Court ruling on the legality of President Donald Trump’s tariffs, pending at the time of this writing, could alter the playing field again. But whatever the outcome, the ports’ investment in increased storage capacity provides flexibility to shippers.

Volumes at Savannah’s container port were robust, even booming, this spring, even as tariff discussions starred in the news cycle. Ports executives attribute that in part to businesses advancing their orders ahead of tariffs they knew were coming. The first decrease that could be linked to tariffs came in June, when Savannah reported a 9.6% decrease compared to June 2024 – perhaps in part due to the front-loaded cargo of the spring. By August, container volumes were up 3.2% compared to last year. In Brunswick, the Roll-on/Roll-off (Ro/Ro) cargo – such as cars, trucks and heavy equipment – was down by 14.3% year-over-year compared to the previous August.

“More important, the market has changed, and we responded very quickly to those needs. It didn’t just accidentally happen. You have to be willing to do things faster.” – Alec L. Poitevint II, chair, Georgia Ports Authority

More Opportunities: Alec L. Poitevint II, chair of the Georgia Ports Authority. Photo credit: Georgia Ports Authority

So, how did one state wind up with two world-class deep-water ports? “It’s been a long-term commitment and forward planning process, says Alec L. Poitevint II, the chair of the Georgia Ports Authority’s board. “We set about to be elite, to be leaders in our sectors. More important, the market has changed, and we responded very quickly to those needs. It didn’t just accidentally happen. You have to be willing to do things faster.”

“I think the political climate creates more opportunities,” he says. “We’re having more manufacturing growth in the United States, and Georgia ports are well positioned to handle that. We’re used to exports as well as imports.”

When it comes to sending out goods versus bringing them in, Georgia’s ports import more than they export, according to Flavio Batista, chief commercial officer for GPA.

“When you look at our mix between exports and imports, we have about 70/30 – 70% imports and about 30% exports,” he says. “Brunswick is a little more balanced, still bigger on exports but maybe 60/40, so we import a lot of cars there, but we also export a lot.”

Bigger Imports: Flavio Batista, chief commercial officer for the Georgia Ports Authority. Photo credit: Frank Fortune

At the container port, some of the top imports, include furniture and goods like tires and floor and wall coverings for big-box retailers like The Home Depot, says Batista. Exports via Savannah include lots of poultry and agricultural forest products and, increasingly, plastic resin – a byproduct of petroleum production which overseas manufacturers use to make plastic goods.

At Brunswick, imports include virtually every name on the road and exports come from the Southeast’s growing inventory of automotive assembly plants. Ro/Ro cargo moving in either direction undergoes the final stages of assembly at the various vehicle processors on or near the ports – a customization process geared toward saving money and time, as well as the particular requirements of the receiving country. Cars bound for Japan, for example, must have their tire-pressure sensors removed because they interfere with police communications in that country, Batista says.

Outpacing the Competition

Brunswick became the nation’s leading port for vehicles and heavy equipment in 2024 – a long-term goal. Whether it can hold on to that title short-term in a tariff-impacted environment remains to be seen, although the same factors would apply to all Ro/Ro ports. But in the long term, GPA officials seem confident of retaining the status. A fourth berth is now under construction, and the Brunswick port has a secret weapon no other auto port has – plenty of land. After all, you can stack containers, but you cannot stack cars, so those acres of pavement come in handy.

Leading the Nation: The Port of Brunswick was No. 1 for vehicles and heavy equipment in 2024. Photo credit: Georgia Ports Authority

The GPA documents its economic impact with formal studies conducted by the University of Georgia Terry College of Business’s Selig Center for Economic Growth. The report for fiscal year 2024 shows the port impacts nearly 651,000 full-and part-time jobs, including logistics, manufacturing and agriculture. It accounted for $174 billion in sales, an increase of $3 billion, or 2%, over FY2023.

“The thing that is most striking to me is the fact that about one job out of every eight [statewide] is dependent on Georgia’s ports. To me, that is the bottom-line number that is most impressive,” says Jeffrey Humphreys, director of the Selig Center.

Other good news from the recent academic research front: Georgia Tech’s Supply Chain and Logistics Institute, in a study entitled “Shipping Variability and Trade Route Decision-Making,” compared shipping from Asia to Atlanta via both West Coast ports and Savannah and found that Savannah was 32% cheaper as well as more predictable and consistent.

In a staff-compiled study assembled from publicly available figures, Savannah reported 8.6% growth in TEUs (20-foot equivalent units, a standard container shipping measurement) in FY2025 (which ended June 30, 2025), while other Southeast ports showed same-period growth of 4.3% in Jacksonville, Florida and 3% in Charleston, whereas Norfolk TEUs declined by 3.6%.

“Our growth should outpace others for the foreseeable future,” Lynch says.