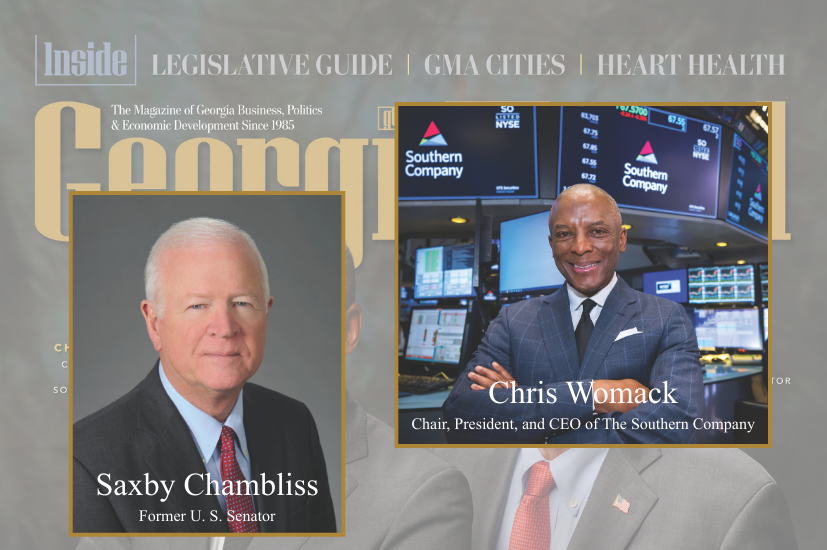

2026 Georgia Trustees

High Honor: Chris Womack, chair, president and CEO of Southern Company, and former U.S. Sen. Saxby Chambliss

It was nearly three centuries ago, in 1732, when King George II of England appointed the first Georgia Trustees to establish the new colony of Georgia upon the principal “not for self but for others.”

Centuries later, in 2008, the Georgia Historical Society and the governor’s office reestablished the tradition by honoring two people each year as Trustees, chosen because both their character and work ethic reflect that motto. To be named a Trustee is considered the highest honor the state can confer.

This year’s Georgia Trustees are former U.S. Sen. Saxby Chambliss and Chris Womack, chair, president and CEO of The Southern Company. The two will formally be honored on April 18 at the Trustees Gala in Savannah.

Like those who preceded them, Chambliss and Womack reflect the ideals of those original trustees. Both seem to have a gift for connecting with others even as they tackle tough issues, making them positive role models to current and former colleagues and their community.

Find out more about these highly regarded leaders on the following pages and all that they have done to receive the honor of being named a Georgia Trustee. – Kathleen Conway

Former U.S. Sen. Saxby Chambliss

Answering the Call

A second career as a politician led Saxby Chambliss to be a strong advocate for Georgians on the Hill.

It almost seems as if Saxby Chambliss was destined for a political career from the time he was a child. His father was an Episcopal priest, and the family moved often – from Warrenton, North Carolina, where Chambliss was born, to South Carolina, back to North Carolina, then to Tennessee, Louisiana, and finally Darien, Georgia. Being the new kid means getting comfortable meeting new people and making new friends quickly – talents that contributed to Chambliss’ easy-going manner and success both as a candidate and then a member of the House and Senate from Georgia.

Taking the Oath: Chambliss’ wife Julianne holds the Bible as he was sworn into the Senate by then Vice President Dick Cheney. Photo credit: contributed

Nevertheless, he wasn’t thinking about a career in politics when he attended the University of Georgia (after a year at Louisiana Tech) – although his ability to shake hands and make friends helped fund his education. Chambliss says that his parents couldn’t afford to pay for two kids in college at the same time (he’s the middle brother of three) so he worked part-time for Athens institution Benson’s Bakery selling fruitcakes on the road to civic clubs and church groups.

“I traveled three summers,” he recalls. “To West Virginia one summer, and the east coast of Florida the next two summers. Then in the fall, I went to night school and worked in the bakery, making fruitcakes.” He deadpans that “I don’t eat fruitcakes now,” but quickly adds that working for the Benson family was a great experience. “They gave me a car, a gas credit card and $10 a day. I thought I was rich.”

Lifechanging Relationships

College Chums and Colleagues: Chambliss met the late U.S. Sen. Johnny Isakson, pictured together at the Georgia Governor’s Mansion, while the two were students at the University of Georgia. Photo credit: contributed

At UGA, Chambliss met two people who would have a profound impact on his life – one was his future colleague in the Senate, the late Johnny Isakson. “I met Johnny within 60 to 90 days after I arrived on campus, and we became good friends,” he says.

Although Isakson jumped into business and then politics not long after graduating from UGA, Chambliss set his sights on law school – and a life with his soon-to-be-wife, Julianne, whom he also met at UGA. The couple wed in 1966 and moved to Moultrie after Chambliss finished law school. For the next 26 years, Julianne taught elementary school while her husband practiced law.

Along the way, he became an expert on agricultural regulations. “The economy of Colquitt County is dictated by the farming community, so during the course of my 26 years practicing law, I did a lot of work for farmers,” he says. Occasionally, he says, a farmer would run afoul of “some rigid guidelines” under a government program, like under- or overplanting the acreage that was allowed. Other than one lawyer in Albany, no one took the time to read the regulations and represent the farmers, Chambliss recalls. “I was almost forced to do it because I had so many clients accused of violating rules and regulations,” he says. “It was a lot of fun and it turned out to be a very lucrative part of our law practice.”

It was also good practice, it turned out, for his second career.

Class Action

In 1992, the political landscape was changing in South Georgia, and Chambliss was recruited by local business leaders to run for Congress. The first vote he had to win was Julianne’s. “I told my wife about it and she started crying,” he says. “I told her, ‘I’m not going to do it unless you’re 150% on board.’ She thought about it overnight and said, ‘I think there’s an opportunity for you to make a contribution as a member of Congress, and I think we ought to do it.’”

He lost the primary, but he and Julianne – who was as deft as the candidate on the trail and integral to his success – never really stopped running. “I just continued basically campaigning without saying, ‘I’m running again,’” he says.

Coordinated Efforts: Chambliss and Isakson worked in tandem on Georgia issues, appearing at this rally to support Delta Air Lines in 2006 when the company was an acquisition target. Photo credit: contributed

In 1994, that campaign prowess coincided with the national “Republican Revolution” that saw conservatives, led by fellow Georgian Newt Gingrich, win the majority in the House for the first time since the 1950s. Chambliss was the first Republican elected in the 8th District since Reconstruction.

“It was a pretty exciting time,” he says. He wanted to be on the Agriculture Committee and the Armed Services Committee – both plum assignments. With Gingrich as Speaker of the House, Chambliss got what he wanted. And although he was known for his solidly conservative record, Chambliss notes that both committees worked in a bipartisan manner – something he also became known for, especially later in the Senate.

“The House is designed by the framers of the Constitution to be very partisan, and I found that was the case,” he recalls. “But when it came to agricultural programs, there were folks like [Democrat] Sanford Bishop, who was the congressman in the next district. We shared the same agricultural issues, so he and I would team up to make sure we protected those programs. … So my bipartisanship actually started in the House, and that’s a little unusual. But once I got to the Senate, it was natural and I had to work with Democrats because you have to have 60 votes to do anything.”

Chambliss survived a redistricting fight that drew Moultrie out of the 8th District (House members aren’t required to live in their districts), and he was reelected three times. In 2001, however – with Democrats still in power in the state legislature and Roy Barnes as the governor – redistricting put Chambliss in the same district as his good friend, Rep. Jack Kingston. That was enough to push him towards a Senate run and he was elected in 2002.

Bipartisan Approach

His expertise in ag, intelligence and the military moved across the Capitol, too. During his two terms in the Senate, he served as chair of the Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry (the only senator since 1947 to chair a full standing committee after serving in the chamber for just two years), and as a member of the Armed Services Committee and the Select Committee on Intelligence. (He had previously chaired the House Intelligence Subcommittee on Terrorism and Homeland Security, which oversaw investigations of the intelligence community after 9/11.)

He was also a founding member and leader, along with Sen. Mark Warner (D-Virginia), of the Gang of Six (later the gang of Eight), a determinedly bipartisan group of senators who sought a practical path to deficit and debt reduction.

“…My bipartisanship actually started in the House, and that’s a little unusual. But once I got to the Senate, it was natural and I had to work with Democrats because you have to have 60 votes to do anything.” Former U.S. Senator Chambliss

And he was reunited with his old friend Isakson, who won the state’s other Senate seat in 2004. “We were the envy of every other senatorial office, with the relationship we had,” Chambliss says. “Those 10 years I had with him [overcame] the other negative issues of being a senator because Johnny was my dear friend, my dearest colleague, and we confided in each other.”

But eventually those other issues – including the collapse of the Gang of Eight’s plan without a vote and ongoing gridlock – helped convince Chambliss to retire at the end of his term in 2014. Isakson paid tribute to his friend on the Senate floor, saying “Georgia has had some great senators: Richard Russell, who was really the master of the Senate; Zell Miller, a former governor of Georgia, a great friend of mine and a great mentor of our state; and Sam Nunn, one of the finest in national defense and foreign policy our state ever offered. Saxby will be the fourth on the Mount Rushmore of Georgia senators who have served Georgia with distinction and with class.”

True to form, Chambliss has remained engaged in bipartisan efforts, like the Democracy Defense Project, an organization of former elected and civic officials committed to defending the U.S. electoral system. Chambliss, former Gov. Barnes and former Atlanta Mayor Shirley Franklin penned an op-ed in the AJC in November 2025 titled “Stop relitigating 2020 election. Voting in Georgia is secure and accessible.”

“I don’t perceive myself to be a great Georgian,” Chambliss says. “I’m just a preacher’s kid from South Georgia who worked hard and was very fortunate to be in the position that I was in Washington due to my wife and a lot of dear friends. But public service is always a calling. And whether it’s as a candidate or working on a campaign or supporting qualified candidates, I hope that every citizen would at some point have that calling.”

ChrisWomack

Positive Energy

Chris Womack was headed for a political career until a decision to join Southern Company supercharged his professional life.

You can be whatever you want to be, Chris Womack’s grandmother told him and his brothers. Don’t accept anyone’s limitations. Pursue your dreams.

Making a Difference: Womack, in front of monitors showing the Southern Company’s figures at the New York Stock Exchange. Photo credit: contributed

Growing up in rural Alabama in the 1960s, that was a powerful message for a young Black child to hear. And Womack took it to heart – although he never thought he’d be a CEO. Mayor, maybe. Instead he’s leading the second-largest U.S. utility as Southern Company’s first Black CEO after 37 years at the company he once thought would be a temporary stop in his career.

Womack’s mother wanted him to be a teacher, like she was. But he was always interested in politics. He recalls his childhood revolving around “church and school and family,” with a lot of time spent with his grandmother, fishing and gardening. “It was kind of a wonderful, simple life,” he says.

It also included city council meetings. “I would ride my bicycle downtown to go to city council meetings and ultimately got to know the mayor,” Womack says. “I was just curious.”

That curiosity led him to study political science at Western Michigan University, where his fraternity – Alpha Phi Alpha – and his professors helped him build on the foundation his grandmother first laid. “I wanted to get out of Alabama and have some different life experiences,” Womack says. Western Michigan fit the bill – certainly the weather was different, he says, but so was the general environment – and Womack served in student government and was active in political causes. (He recalls protesting investment in South Africa during apartheid).

“I always found myself involved politically,” he says. One of his poli-sci professors, David Houghton, became a mentor who helped Womack get an internship with the city manager of Kalamazoo. “It really opened my eyes to see the inside of the city manager’s office – about what the possibilities were, what the job required day-to-day,” he says.

The city manager was a Black man, and that also made an impression on the college student from Greenville, Alabama. “Seeing him in that role also said, ‘OK, I can do this. I can potentially be this,’” Womack says – proof that his grandmother was right.

Houghton also facilitated a summer internship with Ralph Nader. “I fell in love with D.C.,” Womack says. So after a brief stint back home following graduation, he headed to the capital and found a job working as a legislative aide for Leon Panetta, then chair of the House Budget Committee (who later served in the Clinton and Obama administrations).

Panetta became another mentor – a father figure, Womack says. He describes his time on the Hill as “an incredible experience of learning, of understanding the importance of hard work, being challenged to look at matters differently – and how do you fix problems? How do you always look to create things to make circumstances better for people?” Panetta, he says, “always challenged me, and challenged me to be the best I could be” – just as his grandmother had.

Kicker: Womack, center (in light blue), flanked by employees at Alabama Power. Womack, a native Alabamian, started his Southern Company career at Alabama Power. Photo credit: contributed

Power Move

In 1988, Womack once more headed South. “I always had a desire to get back and live in the South and to contribute in some way – to make a difference,” he says. “And I wanted my kids to be near their grandparents.”

He fielded three job offers: one from the University of Alabama at Birmingham, one from Birmingham Mayor Richard Arrington’s office, and one from Alabama Power. Arrington was the first Black mayor of what was then Alabama’s biggest city, and the offer lined up with Womack’s interest in politics.

“I wanted to do the job with the mayor, but something said, ‘Let me try out this power company job for a little while and put something different on my resume,” he says.

He never left, making his way through a number of different roles and responsibilities, starting as a governmental affairs representative and moving through jobs in human resources, power generation and external affairs. Womack likes to say he’s had 14 different careers, all within Southern Company. “I’ve had incredibly different experiences and got to know the people and the company inside and out,” he says. “It’s been an incredible learning experience.”

Womack was serving as executive vice president and president of external affairs in 2020 when he was named president of Georgia Power; he added the CEO and chair titles in 2021. He was named CEO of Southern Company in 2023, becoming the first Black CEO to lead the company and one of only a handful of Black CEOs of Fortune 500 companies in the U.S.

In the time he’s been with the company, Womack has experienced rapid changes in the energy field. “Just how we make electricity,” he says, moving from coal-fired power to natural gas to renewables (solar, wind) and batteries for storage. And the demands are changing rapidly, too, with massive data centers hungry for vast amounts of electricity. “We’ll have power,” Womack is fond of saying.

The challenge, he says, is balancing the ballooning growth and demand from data centers without saddling residential customers with ever-rising prices. “We have to make sure we do this in a way that does not place the burdens of that cost on existing customers as we serve those data centers,” he says. “Part of that means keeping the bill as low as possible as we go through this period.”

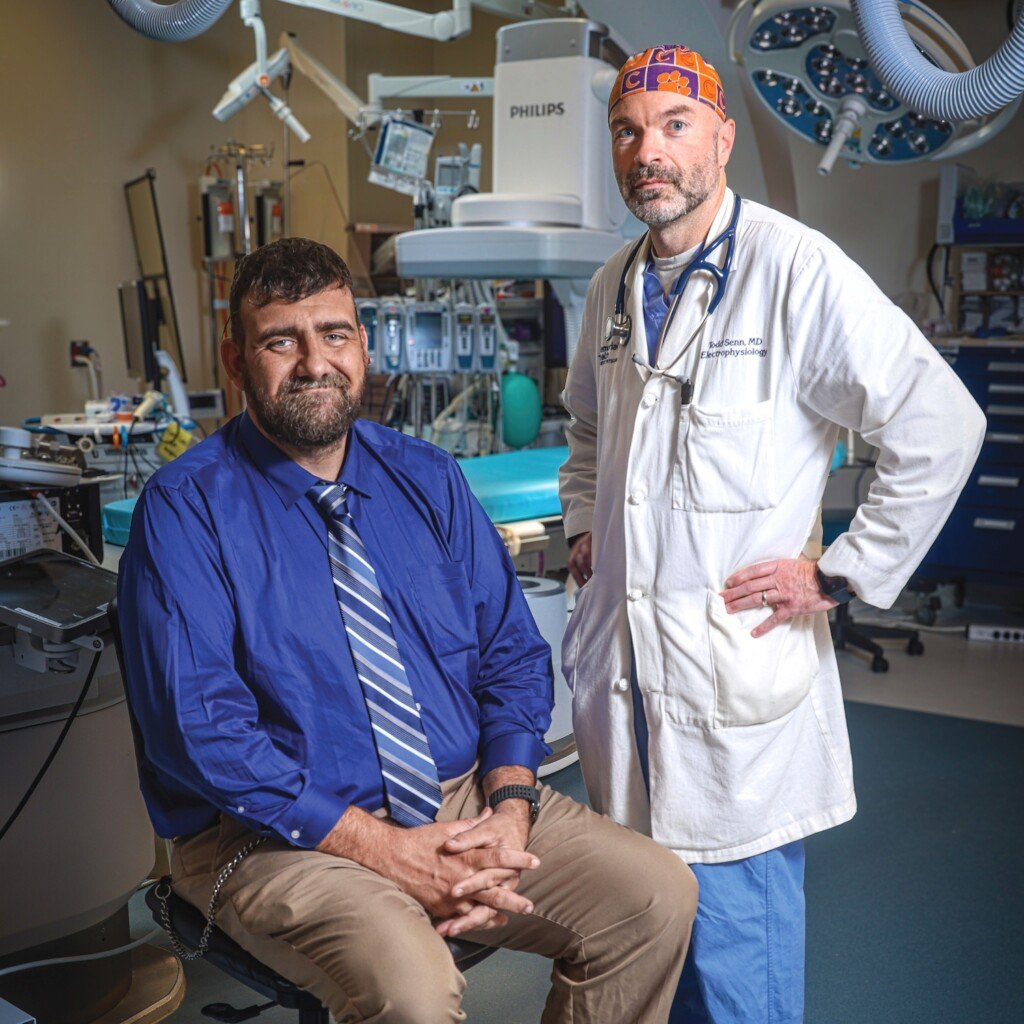

Proximity and Purpose

Womack brings a similar there-will-be-power optimism and conviction to work in other areas, too. Part of Southern Company’s culture is for its employees to be active in their communities – “leading the heart walks and the cancer walks and the Little League teams” as he puts it. “I have a belief in people and our ability to collaborate and work together to meet our objectives and solve problems,” he says. “Always knowing that everything’s going to be OK, we’re going to be good. We’re going to get through whatever we’re facing.

“I’ve had incredibly different experiences and got to know the people and the company inside and out. It’s been an incredible learning experience.” – Chris Womack

“I talk a lot these days about hope, and also about proximity and having a purpose. So as you stay focused on your purpose, we also have to make sure we’re close to people, we’re engaging with people, we’re engaging with communities to understand what people are going through,” he says. “Particularly during periods of chaos, change, transition and uncertainty, it’s critically important to give people hope. That’s what helps us overcome – because there will be trials and tribulations, but we will get through it together and we will be better for it.”

Community Service: Womack, who previously chaired the East Lake Foundation Board of Trustees and remains a member, sits with others holding $1 million check to East Lake Childhood Education Initiative in 2019.

Womack says he feels a responsibility to not only “honor the people whose shoulders I stand on” but to set an example for others to follow. Panetta taught him to not accept the status quo. “That has been a big part of how I see things in terms of, if it doesn’t work, change it. If it doesn’t exist, make it available,” he says. Just as seeing the Kalamazoo city manager made him realize what was possible, he wants others to see him as the first Black CEO of Southern Company and have the same realization. “For everybody to see, ‘This is possible for me,’” he says. “‘If I put in the work, I work well with others, I get results, I demonstrate solid leadership – this is something I too can achieve.’”

He also feels an obligation that he describes as “owing it to the community…to make sure I’m giving back.” For a teacher’s son, that included chairing the Communities in Schools of Georgia, which focuses on keeping at-risk kids in school. He’s also chaired the East Lake Foundation board of trustees and remains a member of the board. And he’s currently co-chair of Partners for HOME’s Atlanta Rising campaign to raise $212 million to end homelessness in Atlanta.

It’s also important to Womack that the community and philanthropic work he does is meaningful, not just commercial. “We don’t live in a bubble – we live in communities, and for a community to be better we all have to lean in and chip in,” he says. “I can’t just take care of myself and my family and not worry about others. I think I have an obligation and responsibility to give back in as many ways as I can.”