Position Without Power?

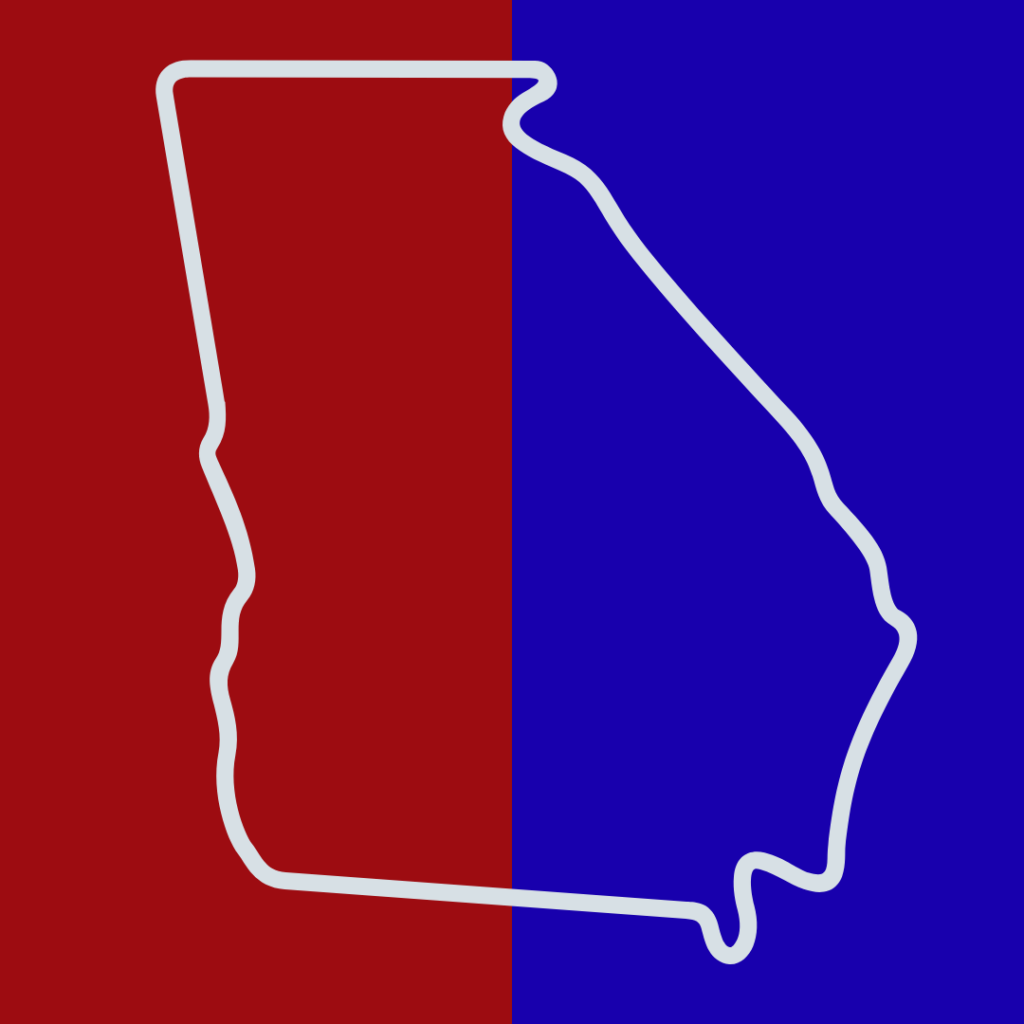

Given our competitive two-party state, it might make sense to consider constitutional change.

Georgia’s last Democratic lieutenant governor, Mark Taylor of Albany, served two terms in that office. In his first term from 1999-2003 he wielded power over the state Senate, where his party still maintained a majority.

At the start of Taylor’s tenure as lieutenant governor, Sonny Perdue – a name you might have heard of – had just switched parties to become a Republican the year before. As a Democratic senator, Perdue had risen through the ranks to become president pro tempore of the Senate, the highest position among the 56 members. With Perdue now in the Senate minority, Taylor bottled up his legislation. When Republicans objected, Taylor infamously replied with, “Cry me a river.”

At the start of Taylor’s tenure as lieutenant governor, Sonny Perdue – a name you might have heard of – had just switched parties to become a Republican the year before. As a Democratic senator, Perdue had risen through the ranks to become president pro tempore of the Senate, the highest position among the 56 members. With Perdue now in the Senate minority, Taylor bottled up his legislation. When Republicans objected, Taylor infamously replied with, “Cry me a river.”

Taylor didn’t foresee in that moment that those he tormented would become his tormenters. Perdue would beat the incumbent Democrat Roy Barnes for governor in 2002, and when he took office in 2003, Republicans, with the help of some party switchers, took a majority in the Senate. Even as Georgians replaced the governor, enough split their ballots to re-elect Taylor as lieutenant governor.

Taylor kept his office space and staff, and he still presided over the chamber from the rostrum, but his days of wielding power had ended.

When Georgia created its lieutenant governor position in the last century, it was a one-party Democratic state, so its creators probably weren’t contemplating a scenario where the lieutenant governorship and the state Senate were controlled by different parties. The seat was elected independently of the governor – that is to say, they don’t run on a ticket. The job provided a successor in the case the governor died or otherwise vacated the office, but it didn’t come with any real constitutional powers.

In 2003, that reality hit Taylor like a frying pan to the face. The new Republican leadership, President Pro Tem Eric Johnson of Savannah and Majority Leader Tom Price of Roswell, rewrote the Senate rules to strip Taylor of any power. Before, the lieutenant governor had authority over committee memberships, chairmanships and which committee would hear each bill introduced.

The new rules created a committee on assignments to handle those responsibilities. The three members were Taylor, Johnson and Price, and the latter two outvoted Taylor 2-1 on every question. Each day, Johnson and Price would go to Taylor’s office to tell him what was going to happen. According to the Republicans, Taylor went from resentful to resigned.

“He just stood up there and banged the gavel,” Johnson says. “That’s all he could do.”

One day the Democrats complained that Johnson wouldn’t let them break for lunch. He stood up, addressed the lieutenant governor, and said, “Cry me a river.”

Even under unified Republican control, the Senate can strip the lieutenant governor of powers. Former Lt. Gov. Casey Cagle lost power for a short time during the last decade before regaining it.

Georgia will have competitive elections up and down the ballot next year, but Democrats have virtually no shot of taking a majority in the state Senate. For now, it’s firmly in Republican control. State Sen. John McLaurin, a Northside Atlanta Democrat, is running for lieutenant governor. If Democrats enjoy a wave election – as often happens for the party that’s not in the White House – there’s a decent chance he could become lieutenant governor.

Winning, however, would be the worst possible outcome for his quality of life. The majority would again strip the position of any powers. He would have an office, a title, a staff and a gavel – and nothing to do as long as the governor didn’t go to the grave or to prison.

With Democratic donors focused intently on re-electing U.S. Sen. Jon Ossoff and flipping the governor’s office, McLaurin will have a hard sell in fundraising: “Give to me so that I can perform utterly meaningless political theater from the rostrum as opposed to directing your dollars to a race that might make a difference!”

Given our competitive two-party state, it might make sense to consider constitutional change. In 2018, South Carolina went from independently electing its lieutenant governor to having the governor and lieutenant governor run as a ticket. The lieutenant governor in that case can preside over the state Senate when needed and have a tie-break vote. Another option is abolishing the position and putting the Senate pro tem as next in the line of succession.

But I can bet what the next lieutenant governor would say to this idea: “Cry me a river.”

Brian Robinson is co-host of WABE’s Political Breakfast podcast. He won a Green Eyeshade award in 2024.