The Legacy and Lessons of John Lewis

In politics, there are a lot of transactional friendships, rooted in the question, “What can you do for me?” It is one of the main reasons that so few people trust politicians, lobbyists or anyone else who passes through legislative chambers more than once a year.

But when I met the late Congressman John Lewis, I quickly realized he was the real deal – a genuine friend who truly cared. I am grateful and proud to say he’s one of the best friends I have ever had, in or out of politics. From the moment I became his campaign manager in his 2008 reelection campaign for Congress, I knew that he was the rare man who lived up to his myth.

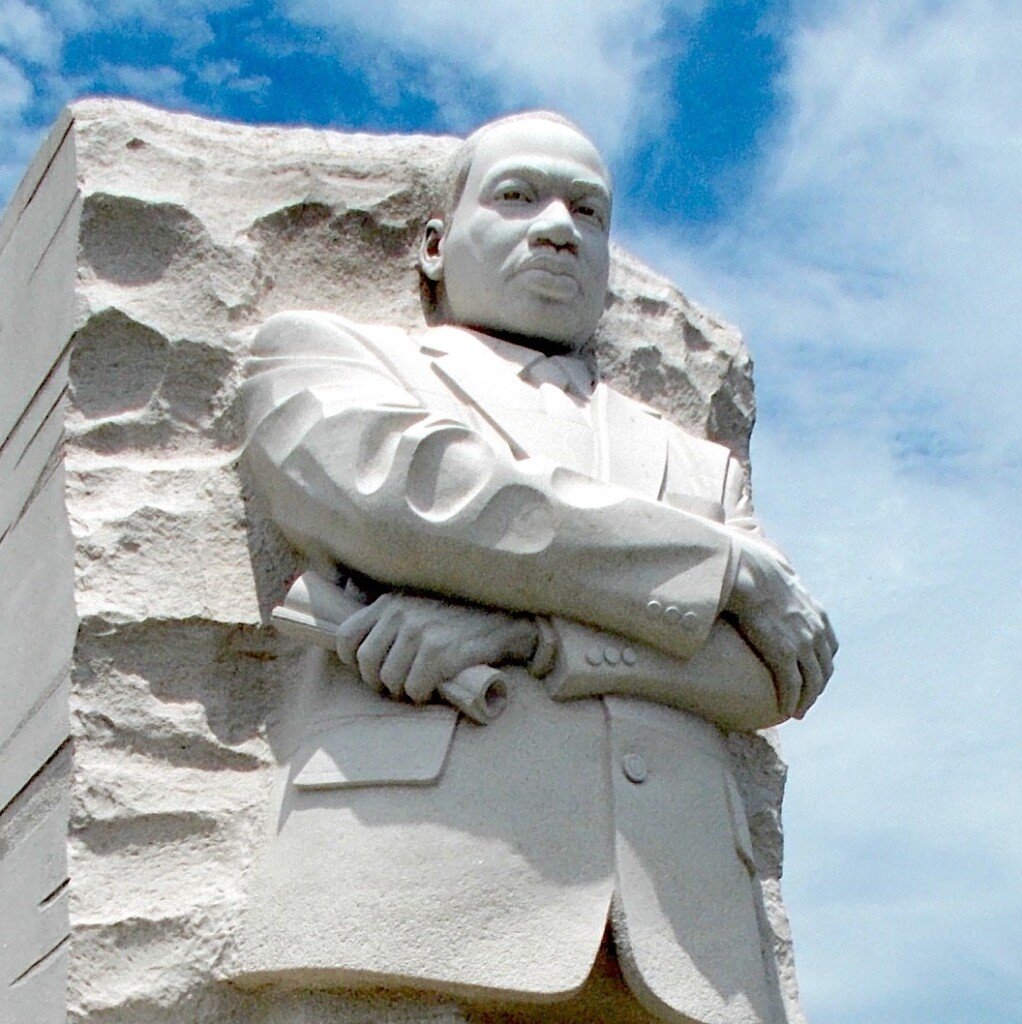

Lewis was a hero of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s – the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee who marched alongside Martin Luther King Jr. in the 1963 March on Washington, where MLK gave his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech. Lewis was the youngest person to speak from the podium that day. He led the first anti-segregation march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge where, in an incident now known as Bloody Sunday, state troopers and police attacked Lewis and other marchers, leaving them beaten and bloodied. Congressman Lewis spent his entire life fighting for what was right, from desegregation in education to equity in healthcare, from his first sit-in to his 33 years in Congress.

One of his greatest passions was voting rights. In his early life, he advocated for equal access to the ballot box for all Americans, particularly Black Americans who may have legally had the right to vote but faced countless barriers to doing so. He was instrumental in getting the Voting Rights Act of 1965 passed, which was designed to prohibit racial discrimination in voting. It was a landmark achievement that reflected the power of getting into what Lewis called “good trouble,” or nonviolent mobilizing and protesting. While the Voting Rights Act reduced racial disparities at the ballot box, we are seeing new efforts to reduce the voting power of people of color 60 years later, with two events laying the groundwork.

The first is the 2013 U.S. Supreme Court decision to gut a key part of the Civil Rights Act, Section 5, which required some states and localities with a history of voting discrimination, many of them in the South, to obtain federal approval before they could make changes to their voting laws or procedures. The decision means the states no longer need to seek federal clearance for new voting changes. A recent study from the Brennan Center for Justice found that between 2012 and 2022, the turnout gap between white and nonwhite voters in counties once covered under Section 5 grew by 9 percentage points, while the gap in noncovered counties went up by 5 points. In other words, nonwhite voting rates lagged the most in these historically discriminatory places.

The first is the 2013 U.S. Supreme Court decision to gut a key part of the Civil Rights Act, Section 5, which required some states and localities with a history of voting discrimination, many of them in the South, to obtain federal approval before they could make changes to their voting laws or procedures. The decision means the states no longer need to seek federal clearance for new voting changes. A recent study from the Brennan Center for Justice found that between 2012 and 2022, the turnout gap between white and nonwhite voters in counties once covered under Section 5 grew by 9 percentage points, while the gap in noncovered counties went up by 5 points. In other words, nonwhite voting rates lagged the most in these historically discriminatory places.

If Lewis were alive today, he would be right back on the streets protesting on behalf of the sacred right to vote.

The second event is the defeat of President Donald Trump in 2020, and the deluge of voter fraud lies that have followed. Georgia appears to have has done everything in its power to suppress turnout in the name of security, from allowing random challenges to voter eligibility to restricting giving someone water in a long voting line – lines that most often occur in precincts with high minority voter populations.

If Lewis were alive today, he would be right back on the streets protesting on behalf of the sacred right to vote. Thankfully, the John and Lillian Miles Lewis Foundation he created is carrying on his work, and I serve on its board of directors. The foundation brings together leaders from across the political spectrum to inform and educate on what he stood for, which will soon be much easier thanks to a new, ongoing effort – mostly funded by Congress – to digitize and archive some three decades of his work which then will be free to the public in perpetuity.

The foundation is also working with local school districts to bring enhanced civics education to schools, beginning in Georgia, so that more kids will grow up with a strong sense of civic duty. Lewis believed that voting was not just a right, but a responsibility, and his foundation is ensuring that his legacy doesn’t just inspire but activates the young people with the power to shape the country.

If voting weren’t so powerful, people wouldn’t be working so hard to take it away from us. For Congressman Lewis, for this country and for its citizens, we can’t let anything stop us from voting this November.