Fighting A-Fib

From smartwatch alerts to ablation advances, there are new ways to treat atrial fibrillation.

On a quiet Friday evening last June, Mary Nash (Mary Nash is not the patient’s real name. It was changed to protect her health privacy.) was sitting on her couch watching TV when her Apple Watch buzzed against her wrist. Expecting an incoming text, she glanced down – but what she saw instead startled her: a notification that the watch had detected an irregular heart rhythm. She dismissed it at first, but when the same alert appeared again two days later, she called her doctor, who worked her in for an appointment the following day. Just days after that first vibration from her watch, Nash was diagnosed with atrial fibrillation (A-fib) and started on a pair of medications – a step she believes may have saved her life.

On a quiet Friday evening last June, Mary Nash (Mary Nash is not the patient’s real name. It was changed to protect her health privacy.) was sitting on her couch watching TV when her Apple Watch buzzed against her wrist. Expecting an incoming text, she glanced down – but what she saw instead startled her: a notification that the watch had detected an irregular heart rhythm. She dismissed it at first, but when the same alert appeared again two days later, she called her doctor, who worked her in for an appointment the following day. Just days after that first vibration from her watch, Nash was diagnosed with atrial fibrillation (A-fib) and started on a pair of medications – a step she believes may have saved her life.

Lifesaving Device: Smartwatches can detect irregular heartbeats and alert people that they might be experiencing atrial fibrillation.

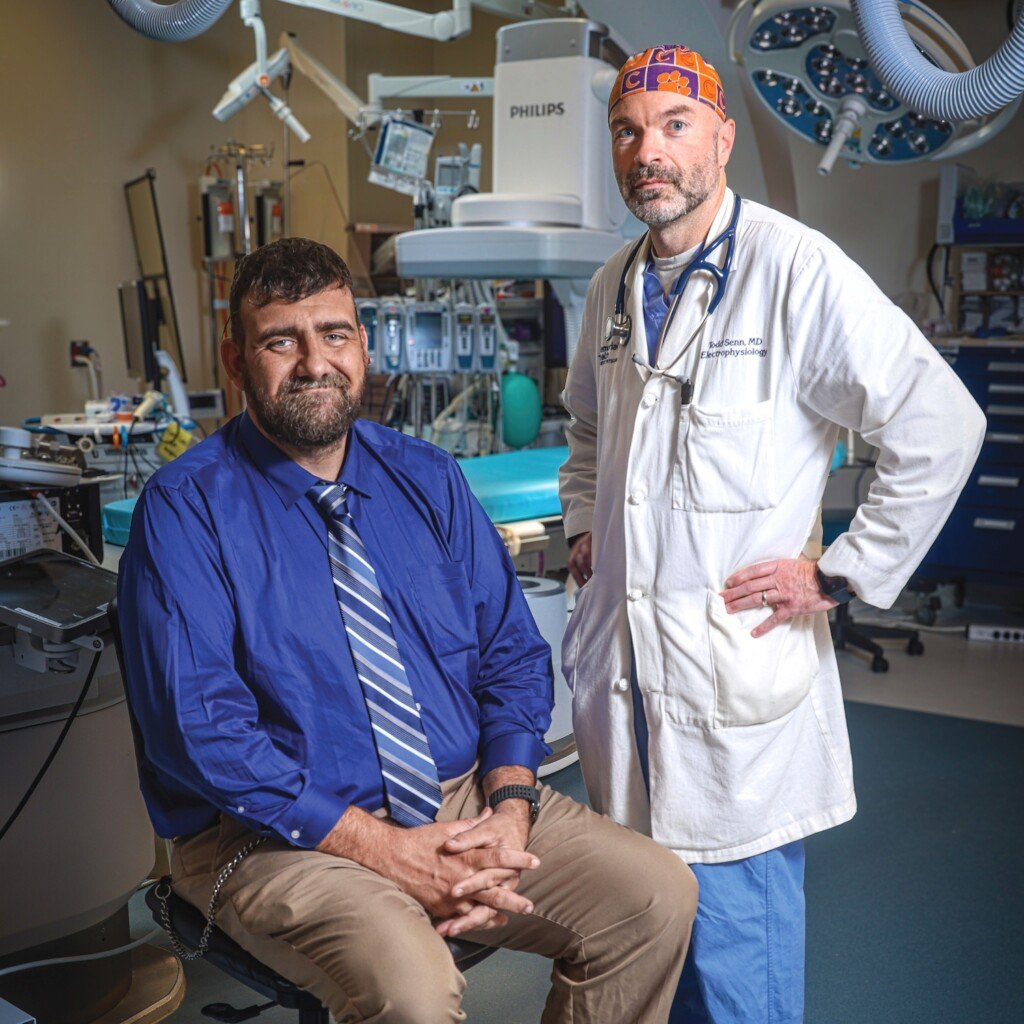

Daniel Smith had been wearing his new Samsung smartwatch – a purchase his wife had considered frivolous at the time – only a short while when he noticed occasional atrial fibrillation alerts. Well familiar with the condition – his mother had suffered complications from A-fib for years – he knew to take it seriously. He scheduled an appointment with his primary physician, who referred him to Dr. Todd Senn, a clinical cardiac electrophysiologist at Memorial Health University Medical Center in Savannah. There, Smith was scheduled for a minimally invasive procedure to restore his heart rhythm and, hopefully, spare him from complications down the line.

Though they may have little else in common, Nash, a retired accountant in Atlanta, and Smith, an areawide foreman for the Georgia Department of Transportation who lives in Eden, are among a growing number of people in Georgia – and across the nation – being diagnosed with atrial fibrillation. The condition is projected to affect more than 12 million Americans by 2030, according to the American Heart Association. While there are no specific projections for how many of those cases will occur in Georgia, doctors say the burden is likely to fall disproportionately on the state. Georgia ranks 16th in the nation for cardiovascular disease prevalence, according to Healthy Georgia: Our State of Public Health (2023), published by the Institute of Public and Preventive Health at Augusta University. Fortunately, Georgia hospitals also employ cutting-edge techniques for treating this growing problem.

Understanding A-fib

The most common type of abnormal heart rhythm in the United States, A-fib affects the upper chambers of the heart. Normally, the heart beats in a regular, organized rhythm. In A-fib, however, the heart experiences “electrical chaotic activity that sets off the chamber to be at a very fast and irregular rate,” says Dr. Chi Zhang, a board-certified cardiologist with Northside Hospital Heart Institute in Atlanta who specializes in treating A-fib. The top chambers can beat as fast as 300 to 400 times per minute, causing the heart to quiver rather than pump efficiently.

“A-fib most often manifests with irregular or rapid heartbeats,” says Dr. Narendra Kanuru, a specialist in cardiology and clinical cardiac electrophysiology with Wellstar Medical Group in Marietta. This irregular rhythm can trigger a wide range of symptoms, including fatigue, lightheadedness and shortness of breath – and, over the long term, serious complications.

But for at least a quarter of people, like Nash and Smith, A-fib can be silent. Even without noticeable symptoms, the condition may still be life-threatening. “When the upper chambers are just fibrillating, so they’re not contracting, there are areas in the upper chamber of the heart where the blood can pool, and when the blood pools there it can form a blood clot and move forward, causing a stroke, which is the biggest risk that we have with A-fib,” says Dr. Murtaza Sundhu, a cardiac electrophysiologist with Georgia Heart Institute in Gainesville, which is part of the Northeast Georgia Health System.

“In fact, people with atrial fibrillation have five to six times higher risk of stroke than the general population,” Sundhu adds. A-fib that is not controlled can also lead to heart failure. That makes recognizing and addressing modifiable risk factors, watching for symptoms and getting an early diagnosis especially important.

Detecting and Diagnosing A-fib

Early Awareness: Dr. Chi Zhang, a cardiologist with Northside Hospital Heart Institute in Atlanta, says the increase in wearable technology has led to more A-fib diagnoses, especially in younger people. Photo credit: Ben Rollins

While age is the biggest risk factor for A-fib – recent national data show an average age in the mid-70s – the condition is increasingly being identified in younger adults. Nash was 72 when her A-fib was diagnosed, but Smith is only 38. Experts believe this trend may reflect rising rates of high blood pressure, diabetes and sleep apnea in younger people; greater awareness of heart rhythm symptoms; and widespread access to simpler diagnostic tools, including wearable devices and improved outpatient monitoring. These shifts mean doctors are catching A-fib earlier and in people who might not have fit the traditional profile even a decade ago.

“Everyone has an Apple Watch nowadays. Everyone has a Whoop bracelet or an Oura ring,” says Zhang. “All of this wearable technology has really picked up usage over the last couple of years. And in doing so, it’s actually allowed us to diagnose a lot more atrial fibrillation, especially in younger patients.”

While diagnosis often begins with a simple wearable device, the rest of the process unfolds in medical settings that rely on far more advanced technology – and on specialists trained to interpret it and treat it. If someone suspects A-fib, either due to symptoms or a smartwatch alert, doctors advise seeing a primary physician right away. “Just because the watch tells you [that] you have A-fib, that doesn’t mean you do. Someone has to review the results,” says Sundhu.

If A-fib is constant, a standard EKG may be enough to make the diagnosis. But more often – especially early in the disease – the irregular heartbeat comes and goes and may not appear on an EKG unless it happens during the test. In those cases, doctors may prescribe a portable, medical-grade heart monitor that you can wear at home. “There are one- or two-day monitors. There are 30-day monitors. And there are even very, very miniaturized implantable devices that we put just under the skin that can monitor the patient’s heart rhythm for up to five years,” says Kanuru.

“Let’s say, for example, someone came to the hospital, and they had a stroke, and we had no idea of the cause. Having a monitor to keep watch on their heart rhythm long term may be beneficial, because even though we can’t stop the stroke that already happened, if we find atrial fibrillation, medical therapies and interventions can reduce the risk of stroke by well over 90%,” he says.

Treating Atrial Fibrillation

Reviewing Results: Dr. Narendra Kanuru, a specialist in cardiology and clinical cardiac electrophysiology with Wellstar Medical Group in Marietta. Photo credit: Contributed

There are two major goals when treating A-fib: preventing dangerous complications – especially stroke – and managing the irregular heart rhythm itself.

“I tell my patients atrial fibrillation is a two-headed monster,” says Senn. “There’s the rhythm side of the disease that makes people feel bad, and then there’s the risk side of the disease – that’s the risk of stroke.”

Which treatment a person receives depends on which “side” of A-fib is being addressed, as well as factors such as symptom severity, underlying health conditions and stroke risk. Georgians benefit from access to a growing number of advanced therapies now available at major medical centers across the state.

“In fact, people with atrial fibrillation have five to six times higher risk of stroke than the general population.” – Dr. Murtaza Sundhu, cardiac electrophysiologist, Georgia Heart Institute

Preventing Complications

For many people – including Nash – treatment to prevent complications begins with prescription blood-thinning medications. “I’m not talking about baby aspirin or stuff like that, because they are not blood thinners. They are anti-platelets,” says Sundhu.

Today, the most commonly used medications are a class of drugs called direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs). They include apixaban (Eliquis), rivaroxaban (Xarelto) and dabigatran (Pradaxa). These anticoagulants, introduced within the past decade, work by blocking proteins in the blood that help it to clot. They are highly effective at preventing stroke and tend to carry less risk and need less monitoring than older anticoagulants such as warfarin (Coumadin). Still, they aren’t right for everyone.

For people who have bleeding risks or other problems taking blood thinners, multiple Georgia medical centers offer minimally invasive implants known as the Watchman and the Amplatzer Amulet (Amulet). The procedure seals off a small, pouch-like pocket, called the left atrial appendage, in the heart where clots can form during A-fib. This prevents clots from entering the bloodstream. During the procedure, doctors guide a small plug-like device into the pocket through a catheter inserted in the leg. Over time, heart tissue grows over the device, creating a permanent closure that reduces stroke risk without needing to take blood thinners.

Restoring Rhythm

As with preventing complications of A-fib, medications are typically the first line of treatment for controlling symptoms and stabilizing the heart’s rhythm. While common heart medications like beta blockers or calcium channel blockers can slow the heart rate and help reduce symptoms, restoring normal rhythms requires medications that work directly on the heart’s electrical system. These are called antiarrhythmic medications.

“All of this wearable technology has really picked up usage over the last couple of years. And in doing so, it’s actually allowed us to diagnose a lot more atrial fibrillation, especially in younger patients.” – Dr. Chi Zhang, board-certified cardiologist, Northside Hospital Heart Institute

“These medicines aren’t perfect, but they are successful statistically 60% of the time,” says Kanuru.

Because each kind of antiarrhythmic drug works differently and has specific safety considerations, doctors choose the right drug carefully and often monitor patients closely when starting treatment.

Cardioversion

Advanced Therapies: Dr. Michael Omar is a cardiologist with the Southeast Georgia Health System in Brunswick. Photo credit: Eliot VanOtteren

In some cases, treatment involves both medications and procedures, including cardioversion – a technique that delivers a controlled electrical shock to restore the heart’s normal (sinus) rhythm. “Sometimes I explain this to people like we’re just flipping a switch to reset the rhythm back to normal,” says Dr. Michael Omar, a cardiologist with the Southeast Georgia Health system in Brunswick.

For some people, a single cardioversion keeps A-fib at bay for a long time. But for others, like 57-year-old Marty Anker of Alpharetta, the benefit can be fleeting. Up to half of people who undergo cardioversion see their A-fib return within a year – and for many, it can happen much sooner.

When doctors recommended cardioversion for Anker’s A-fib, which they believed was tied to scar tissue from heart surgery he had at age 18, the procedure initially worked. “That worked for about 24 hours. I was back in rhythm, and literally a day and a half later I was back into A-fib. So it didn’t solve the problem,” says Anker.

Ablation and Other Procedures

When cardioversion is not successful – or sometimes even as an initial treatment – doctors often recommend ablation, a technique that restored normal rhythm for both Smith and Anker.

Ablation involves threading thin catheters through a vein in the groin up to the heart to destroy the small areas of tissue responsible for triggering the irregular rhythm. Traditionally, ablation has relied on heat (radiofrequency) or cold (cryoablation), but both Anker and Smith received a newer type of therapy called pulsed field ablation (PFA). Anker was the first person in the state to receive FaraPulse, an advanced platform for delivering pulsed-field ablation, at Northside Heart Institute.

Instead of heat or cold, PFA uses “essentially high-energy electrical pulses of energy to destroy the tissue in a more controlled fashion,” says Zhang. “So it typically results in less inflammation. It’s safer around more sensitive tissues such as blood vessels, lung tissue, nerve tissues. And it allows the procedure to be performed much faster compared to traditional conventional ablation.”

Surgical Solutions

For people with special circumstances – such as A-fib that hasn’t responded to other treatments or is longstanding – other surgeries are available.

“At Savannah Memorial, we are able to do a combination procedure where an ablation and closure of the left atrial appendage are done at the same time. So it’s one procedure, one anesthesia, one hospitalization, and both sides of the coin – both parts of the disease are being dealt with and managed at the same time,” says Senn.

Other options for longstanding persistent A-fib include the robotic Maze procedure and AV node ablation with pacemaker implantation. The robotic Maze procedure is a minimally invasive surgery in which doctors make precise incisions in the heart. “Then they create scars within the heart itself to block the short circuit causing A-fib,” says Omar. “Sometimes we have to reach for something as advanced as that, but only if the risks are worth taking.”

In an AV node ablation with pacemaker implantation, doctors use ablation to intentionally block the electrical pathway that sends signals from the atria to the lower heart chambers (ventricles). By stopping this connection, the ventricles are shielded from the chaotic electrical activity of A-fib. Because the ventricles can no longer receive signals on their own, a pacemaker is implanted to create a steady, reliable heartbeat going forward, says Sundhu.

A-fib Management

Doctors say the future of A-fib treatment includes better understanding of A-fib triggers, advances in catheter technology and procedures increasingly tailored to each person’s anatomy. Early diagnosis is also emerging as a key part of better outcomes, and wearable devices are helping alert people to possible A-fib sooner – encouraging them to seek care when treatments can make the biggest difference.

“The data show that earlier upfront rhythm control and treating things a bit more aggressively yields better outcomes in these patients and helps prevent long-term issues with heart failure, heart disease and stroke by addressing atrial fibrillation early on in the disease course,” says Zhang.

Both Nash and Smith believe the alerts they received on their smartwatches enabled them to get treatment before A-fib could do damage.

“In my mother’s case, she got really sick before she found it and it had already done a lot of damage,” says Smith, who lost his mother to A-fib complications shortly after he had his ablation procedure.

Omar assures his patients that “it’s quite possible to live a long, healthy life” with prompt, proper management. “Even in advanced cases, we are constantly developing more advanced therapies that are effective and safe for its management,” he says. “Once a diagnosis of A-fib is made, half the battle is already won.”

How to Lower Your Risk of A-fib

How to Lower Your Risk of A-fib

- While the greatest risk factor for atrial fibrillation – age – is something none of us can change, there are plenty of risk factors we can control, says Dr. Murtaza Sundhu, a cardiac electrophysiologist with Georgia Heart Institute in Gainesville. Managing them can make a meaningful difference in lowering your risk or reducing how often A-fib occurs.

- Avoid alcohol completely. “If you drink alcohol, there is no amount of alcohol that is safe. The [belief] that one glass of wine is good for you is a myth,” says Sundhu. And its effect is surprisingly quick. “We know that even a single alcoholic drink increases your chances of having atrial fibrillation in the next two to four hours.”

- Treat sleep apnea. Frequent nighttime awakenings, heavy snoring, daytime sleepiness or nodding off while watching TV are common red flags. Untreated sleep apnea is a powerful trigger for A-fib, and evaluation and treatment can reduce episodes.

- Maintain a healthy weight. A BMI over 28 increases the risk of A-fib, and each five-point increase above that raises risk even more. Sundhu advises his patients who are overweight or obese to lose about 10% of their body weight.

- Exercise consistently. Heart-healthy activity – 30 minutes, three to four times per week – helps strengthen your cardiovascular system and lowers A-fib risk.

- Control chronic conditions. Keeping blood pressure below 130, managing diabetes and avoiding tobacco smoking all help reduce your burden of A-fib, Sundhu says.