A Win in Name Only

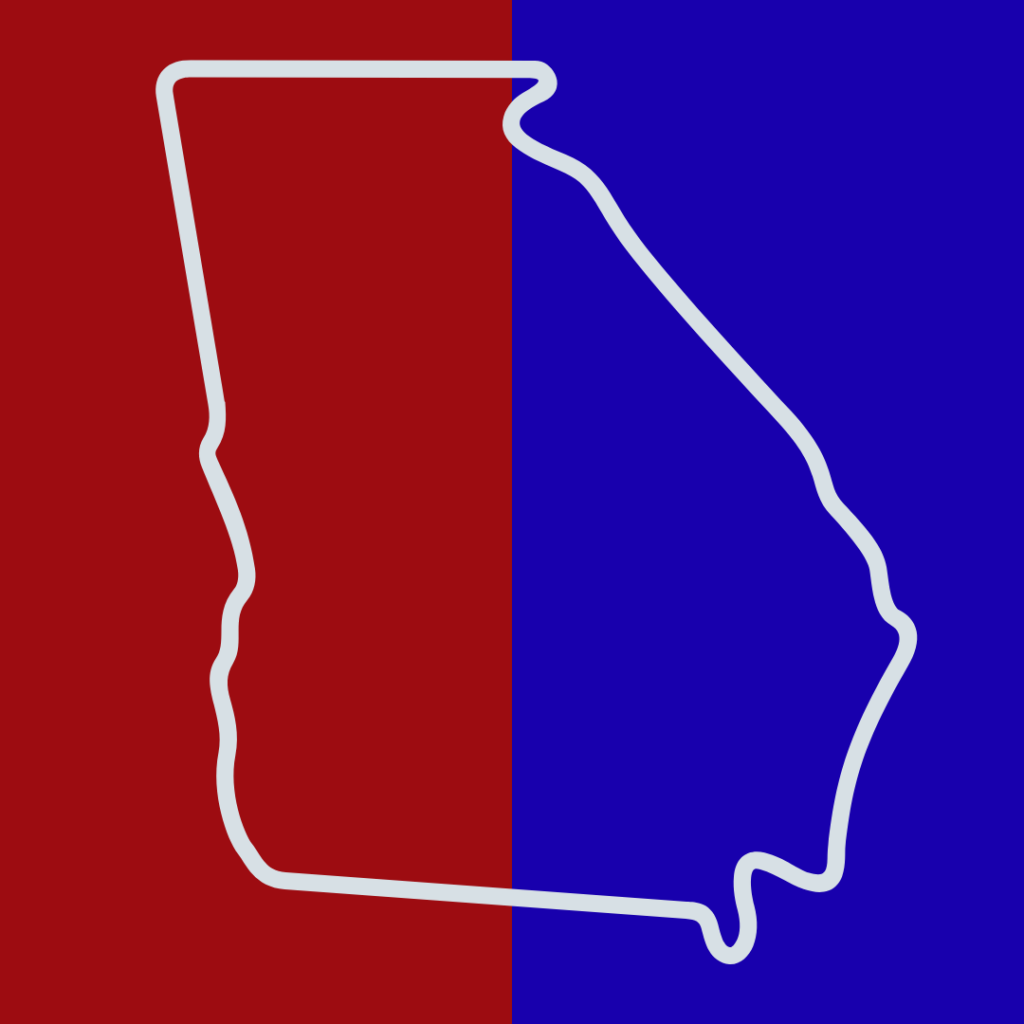

The process didn’t go like they’d wished, and in fact led to dissension and disarray among General Assembly Democrats.

Georgia Democrats learned a painful lesson of “be careful what you wish for.”

Plaintiffs aligned with Democratic groups successfully sued the state of Georgia on claims that the state legislative and congressional maps passed in 2021 didn’t create enough Black majority districts – ones where Black voters can elect “a candidate of choice.”

As a result, the Republican-led General Assembly had to hold a special session that began the last week of November to redraw the lines for congressional and state legislative districts.

As a result, the Republican-led General Assembly had to hold a special session that began the last week of November to redraw the lines for congressional and state legislative districts.

U.S. District Court Judge Steve Jones presided over the cases. Many Democrats assumed that adding Black majority seats would mean more Democratic seats. They discovered that’s not how this works.

The plaintiffs’ case gave them a win in name only. The process didn’t go like they’d wished, and in fact led to dissension and disarray among General Assembly Democrats.

Some Democratic incumbents got paired together in newly drawn districts, causing at least two to announce they wouldn’t run again, and some white Democrats’ districts transformed into a Black majority. Hopes for partisan gains were dashed, as the new maps will largely maintain the partisan balance already in place, though Democrats will target a Republican state House district between Macon and Milledgeville that became majority Black.

Jones, an Obama appointee, ruled that the new maps followed his order. He is widely respected across the aisle. No serious observer could look at his record and call him a partisan hack. Jones upset Democrats, for example, when he ruled against Stacey Abrams’ claims that voter suppression led to her loss in the 2018 governor’s race.

That ruling gives him credibility with conservatives as an objective, fair jurist who adheres to the law. As such, if Jones had decreed that the new maps didn’t meet the requirements of federal law, I would trust his judgment.

Accepting the premise that Jones’ opinion upholds the law as written, we must question whether the law itself has outlived its need. The ruling was based on the requirements of the U.S. Voting Rights Act, passed in 1965 to end the Jim Crow measures that denied Black Americans their voting rights. It ensured that Black Americans could not only vote but have the chance to elect Black candidates.

Today – thanks in part to a “motor voter” law signed by then-Gov. Nathan Deal, a Republican – about 95% of Georgia’s eligible voters are registered, and our elected officials reflect the racial and ethnic diversity of our state.

At the risk of oversimplification, the Black population is one-third of the state, and Black representation in the state Senate is exactly one-third; in the state House it’s slightly less than one-third, and in the congressional delegation it’s slightly more than one-third. This of course doesn’t account for the growing number of state legislators from other demographic groups, reflecting the diversity of a county like Gwinnett where the schools have students who speak more than 100 different languages.

While race no doubt still plays a role in politics, it’s now less important. That’s how the same electorate re-elected both a conservative white governor and a liberal Black U.S. senator in 2022. When U.S. Rep. Lucy McBath, a Black woman, first won her seat in Congress in 2018, the district that elected her was 58% white.

Our U.S. Constitution has stood the test of time because it’s brilliantly vague, so we should take note when it’s specific. The Constitution explicitly grants state legislatures the power to draw congressional district lines. Congress and federal courts should tread carefully when overruling a state’s constitutional prerogative.

We no longer live in a state where Black citizens can only win an election or have their voice heard if they live in a majority Black district. U.S. Chief Justice John Roberts, a Republican appointee now considered the center of the court, foretells a day when

federal policies will acknowledge this progress. “It is a sordid thing, this divvying us up by race,” he wrote in one opinion.

The federal intervention of the past was desperately needed to fix a clear wrong. The facts show the Voting Rights Act worked.

After nearly 60 years, Congress and the courts shouldn’t let a law that changed America for the better diminish itself by becoming an instrument of hair splitting on district lines.

Brian Robinson is co-host of WABE’s Political Breakfast podcast.